<p>By Beverly Faye Hugo (Iñupiaq), 2009<br></p>

<p><strong>Sea, Land, Rivers</strong><br></p>

<p>There’s ice and snow, the ocean and darkness – darkness in the winter and twenty-four hours of daylight in the summer. Barrow was originally called Utqiaġvik (meaning, “the place where <em>ukpik</em>, the snowy owl, nests”). That’s where my people, the Iñupiat, have survived and lived, and I am doing as they have done. On the Arctic coast you can see vast distances in all directions, out over the ocean and across the land. The country is very flat, with thousands of ponds and lakes, stretching all the way to the Brooks Range in the south. It is often windy, and there are no natural windbreaks, no trees, only shrubs. Beautiful flowers grow during the brief summer season. The ocean is our garden, where we hunt the sea mammals that sustain us. Throughout the year some seasonal activity is going on. We are whaling in the spring and fall, when the bowheads migrate past Barrow, going out for seals and walrus, fishing, or hunting on the land for caribou, geese, and ducks.</p>

<p>Whaling crews are made up of family members and relatives, and everyone takes part. The spring is an exciting time when the whole community is focused on the whales, hoping to catch one. The number we are permitted to take each year is set by the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission and the International Whaling Commission. Whaling is not for the faint of heart. It can be dangerous and takes an incredible amount of effort – getting ready, waiting for the whales, striking and pulling and towing them. But the men go out and do it because they want to feed the community. Everyone has to work hard throughout the whaling season. People who aren’t able to go out on the ice help in other ways, such as buying supplies and gas or preparing food. You have to make clothing for them; they need warm parkas, boots, and snow pants.</p>

<p>We believe that a whale gives itself to a captain and crew who are worthy people, who have integrity – that is the gift of the whale. Caring for whales, even after you’ve caught them, is important. After a whale is caught and divided up, everyone can glean meat from the bones. Each gets his share, even those who don’t belong to a crew. No one is left out.</p>

<p>We are really noticing the effects of global warming. The shorefast ice is much thinner in spring than it used to be, and in a strong wind it will sometimes break away. If you are out on the ice, you have to be extremely conscious of changes in the wind and current so that you will not be carried off on a broken floe. We are concerned as well about the effects of offshore drilling and seismic testing by the oil companies. They try to work with the community to avoid problems, but those activities could frighten the whales and be detrimental to hunting.

</p>

<p><strong>Community and Family</strong>

</p>

<p>Iñupiaq residents of Barrow, Wales, Point Hope, Wainwright, and other coastal communities, are the Taġiuqmiut, “people of the salt.” People who live in the interior are the Nunamiut, “people of the land.” The Nunamiut used to be nomadic, moving from camp to camp with their dog teams, hunting and fishing to take care of their families. They packed light and lived in skin tents, tracking the caribou and mountain sheep. My husband, Patrick Hugo, was one of them. For the first six years of his life his family traveled like that, but when the government built a school at Anaktuvuk Pass in 1959 they settled there.</p>

<p>My parents, Charlie and Mary Edwardson, were my foremost educators. They taught me my life skills and language. When I came to awareness as a young child, all the people who took care of me spoke Iñupiaq, so that was my first language. Our father would trap and hunt. We never went hungry and had the best furs for our parkas. Our mother was a fine seamstress, and we learned to sew by helping her. My mother and grandmother taught us to how to care for a family and to do things in a spirit of cooperation and harmony.</p>

<p>I was a child during the Bureau of Indian Affairs era, when we were punished for speaking Iñupiaq in school. My first day in class was the saddest one of my young life. I<em> had</em> to learn English, and that was important, but my own language is something that I value dearly and have always guarded. It is a gift from my parents and ancestors, and I want to pass it on to my children and grandchildren and anyone who wants to learn.

</p>

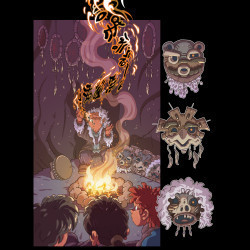

<p><strong>Ceremony and Celebration</strong>

</p>

<p><em>Nalukataq </em>(blanket toss) is a time of celebration when spring whaling has been successful. It is a kind of all-day picnic. People visit with friends and family at the windbreaks that the crews set up by tipping the whale boats onto their sides. At noon they serve <em>niġliq</em> (goose) soup, dinner rolls, and tea. At around 3:00 P.M. we have <em>mikigaq</em>, made of fermented whale meat, tongue, and skin. At 5:00 they serve frozen <em>maktak</em> (whale skin and blubber) and <em>quaq</em> (raw frozen fish). It’s wonderful to enjoy these foods, to talk, and catch up with everyone at the end of the busy whaling season.</p>

<p><em>Kivgik</em>, the Messenger Feast, was held in the <em>qargi</em> (ceremonial house). The <em>umialgich</em> (whaling captains) in one community sent messengers to the leaders of another, inviting them and their families to come for days of feasting, dances, and gift giving. They exchanged great quantities of valuable things – piles of furs, sealskins filled with oil, weapons, boats, and sleds. That took place until the early years of the twentieth century, when Presbyterian missionaries suppressed our traditional ceremonies, and many of the communal <em>qargich</em> in the villages were closed down.</p>

<p>In 1988, Mayor George Ahmaogak Sr. thought it was important to revitalize some of the traditions from before the Christian era, and <em>Kivgik</em> was started again. Today it is held in the high school gymnasium. People come to Barrow from many different communities to take part in the dancing and<em> maġgalak</em>, the exchange of gifts. You give presents to people who may have helped you or to those whom you want to honor. <em>Kivgiq</em> brings us together as one people, just as it did in the time of our ancestors.</p>

<p>Note: This is shortened version of a longer essay from the Smithsonian book <em>Living Our Cultures, Sharing Our Heritage: The First Peoples of Alaska</em>.</p>

<hr>

<p>Tags: Iñupiaq, Inupiaq, Alaska Native, Indigenous, Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center in Alaska, whale, whaling, human geography (#arcticstudies)</p>

Dawn Biddison

20

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison

Dawn Biddison