Phoebe Hillemann

Teacher Institutes Educator

Smithsonian American Art Museum

As the Teacher Institutes Educator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, I organize our week-long summer institutes for middle and high school English and social studies teachers: http://americanart.si.edu/institutes. I'm interested in interdisciplinary thinking, arts integration, and the power of dialogue in learning spaces.

Phoebe Hillemann's collections

Reading American Art as a Historical Source

<p>How can American art be read as a historical text? How can it be used to explore the 2018 National History Day theme of "Conflict and Compromise in History"? This collection examines two works of American art closely, modeling the process of historical inquiry and analysis. It also shares several online resources on reading artwork in a historical context, and suggests additional artworks from SAAM's collection that might support the theme of Conflict and Compromise.</p>

<p>#NHD2018 #NHD</p>

<p>Keywords: Reconstruction, Civil War, John Rogers, Winslow Homer<br></p>

<p><em>#historicalthinking</em></p>

<p><br></p>

Phoebe Hillemann

Phoebe Hillemann

30

Urbanized America: The American Experience in the Classroom

The early years of the twentieth-century saw a significant increase in economic inequality between the wealthiest Americans and the poorest. While the rich continued to bathe in their unregulated, post-industrial age economic success, the poor, largely represented by the overwhelming influx of new immigrants, remained trapped in an unrelenting cycle of poverty and adversity. Many struggled to find prosperity and acceptance in a country where some American citizens harbored foreign resentment and racism. Emblematic of the hardships they encountered is artist Everett Shinn’s chaotic scene of Lower East Side Jewish immigrants being evicted from their homes. This scene in downtown New York City is starkly contrasted with artist Childe Hassam’s romanticized view of an ethereal woman in her uptown home surrounded by beautiful objects likely acquired through European travel. She represents the prosperous post-industrial age, where wealthy patrons demonstrated their cultural sophistication through the acquisition and display of exotic, priceless objects in their homes.<br /><br />

The expanding urban population precipitated the introduction of new building materials in the development of high-rise buildings and tenements, revolutionizing urban living. Technological innovations like the electrified elevator and the Bessemer steel process replaced older building techniques and enabled the construction of high-rise buildings, the new symbols of American progress. However, overcrowding of the evolving urban landscape also gave rise to problems such as poverty, disease, and lawlessness. These issues ultimately led to crucial social reform and legislation, known collectively as Progressivism.<br /><br /><a href="http://americanexperience.si.edu/historical-eras/modern-united-states/pair-eviction-tanagra/">http://americanexperience.si.edu/historical-eras/modern-united-states/pair-eviction-tanagra/</a>

Phoebe Hillemann

Phoebe Hillemann

21

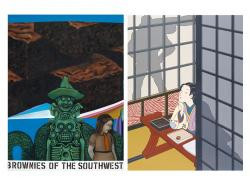

Cultural Imagery and Stereotypes: The American Experience in the Classroom

<p>This collection focuses on two works that deal with the issues of nationality, identity and the assimilation of cultures. Mel Casas's pun-laced <em>Humanscape 62</em> combines elements familiar to many Americans: brownie desserts and a young Girl Scout (a Brownie), with traditional Mexican imagery. This pop art style-blend illustrates the Chicano experience to American culture and creates a push and pull narrative about Latino identity. Similarly, Roger Shimomura, an American-born artist of Japanese descent, contemplates repressed emotions from the time he and his family spent in World War II-era Japanese internment camps, following the attack on Pearl Harbor.</p>

<p>#APA2018</p>

<p><a href="http://americanexperience.si.edu/historical-eras/contemporary-united-states/pair-humanscape-diary-december-12/">http://americanexperience.si.edu/historical-eras/c...</a> </p>

Phoebe Hillemann

Phoebe Hillemann

14

Japanese American Incarceration through Art and Documents

<p>These resources can be used in an activity that introduces a lesson on Japanese American Incarceration during World War II. </p>

<p>1. To begin, show students Roger Shimomura's painting entitled Diary: December 12, 1941. Without providing any background information, use the "Claim, Support, Question" routine to have students make claims about what they think is going on in the artwork, identify visual support for their claims, and share the questions they have about the painting. Document responses in three columns on large chart paper or a whiteboard.</p>

<p>2. Following this initial conversation, share the title, artist's name, and date of the painting. Ask students to consider the date in the title, and discuss what significance this date might have. If they don't figure out that this date was five days after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, share that information. Share with students that this painting is part of a series Roger Shimomura created based on the wartime diary entries of his grandmother, Toku, who was born in Japan and immigrated to Seattle, Washington in 1912. Along with thousands of other people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast during World War II , Toku and her family were forcibly relocated to an incarceration camp after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Roger was a young boy during World War II, and remembers spending his third birthday in the Puyallup Assembly Center on the Washington state fairgrounds, where his family was sent before being transferred to Minidoka Reservation in Idaho for the duration of the war.</p>

<p>3. Jigsaw Activity, Pt. 1. After sharing this context, tell students they will each be receiving a primary source document that relates to the painting in some way. Distribute copies of "Woman at Writing Table," the Superman comic, the Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry, and Toku Shimomura's diary entries. Divide students into four groups, one per document. Give students time to analyze their document as a group and discuss how it affects their interpretation of the painting.</p>

<p>4. Jigsaw Activity, Pt. 2. Next, create new groups so that each group includes students who received each of the four sources. Ask students to briefly report on their document and what their original group discussed as its possible meaning and relation to Roger Shimomura's painting.</p>

<p>5. Return to the painting as a large group, and discuss how the primary source documents have influenced students' reading of the artwork. </p>

<p>6. Optional additional resource: If time allows, have students watch excerpts from Roger Shimomura's artist talk at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.</p>

<p>#APA2018</p>

<p><em>#visiblethinking</em><br></p>

Phoebe Hillemann

Phoebe Hillemann

9

The Subway

Artworks, photographs, and other documents relating to the New York subway system.

Phoebe Hillemann

Phoebe Hillemann

8