Nicole Vance's collections

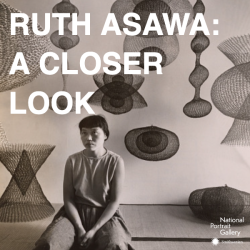

Ruth Asawa: A Closer Look

<p>Learn more about artist Ruth Asawa and her wire sculptures through portraits!</p>

<p>#NPGteach</p>

<p>Keywords: Asian American, Artist, Sculpture, Photographs, Portraiture</p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

17

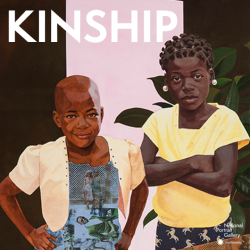

Explore! at the National Portrait Gallery

<p>This Learning Lab collection complements the National Portrait Gallery student Program, Explore!</p>

<p></p>

<p>The Explore! program introduces young students to portraiture. They will be exposed to what makes up a portrait and search portraits for clues to learn more about themselves and significant Americans. Through interactive discussions and hands-on activities, students will read, compare, and contrast portraits across the collection.</p>

<p></p>

<p>After completing this lesson, students will be better able to:<br></p>

<ul><li>Identify key components of a portrait and discuss what we can learn about the sitter through these components.</li></ul>

<p>#NPGteach</p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

63

Detectives de Retratos

<p>Este Laboratorio de aprendizaje (Learning Lab) es un complemento del programa escolar 2020-2021, Detectives de Retratos, de la Galería Nacional de Retratos.</p>

<p>Los estudiantes se transformarán en detectives de retratos, e investigarán retratos y analizarán pistas para ampliar sus conocimientos acerca de personajes relevantes de los Estados Unidos. A través de debates interactivos y actividades de dibujo y escritura, los estudiantes podrán interpretar, comparar y contrastar retratos de toda la colección. Para ofrecer un mejor apoyo para el plan de estudios y favorecer los intereses de los estudiantes, este módulo está dividido en los siguientes temas: presidentes, activistas, íconos y científicos.</p>

<p><strong>Objetivos:</strong></p>

<p>Después de completar esta lección, los estudiantes estarán mejor preparados para: </p>

<ul><li> Identificar a estadounidenses importantes y analizar sus contribuciones a la historia de los Estados Unidos </li><li> Identificar los componentes claves de un retrato y analizar lo que podemos aprender sobre la figura retratada a través de estos componentes.</li></ul>

<p><strong></strong><strong>Enlaces de los planes de estudios:</strong></p>

<p>Este plan de clases es adecuado para alumnos de jardín de infantes a 3.er.

Grado (K-3) en las áreas de estudios sociales, artes del lenguaje y artes visuales.</p>

<p><a href="https://npg.si.edu/teachers/school-groups">Prepare</a> un programa virtual de Detectives de retratos con educadores de la Galería Nacional de Retratos.</p>

<p>#NPGteach</p>

<p>Palabras clave: estadounidenses famosos, presidentes, íconos, activistas, promotores de la justicia social, científicos, inventores, músicos, artistas, retratos, arte, celebridades, cantantes<br><br></p>

<p>La traducción de este recurso fue posible gracias al generoso patrocinio de Bank of America.</p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

75

Expanding Roles of Women: Sparking Civic Engagement Assessment

<p>This Learning Lab collection can be used as an assessment conclusion to the study of the portraits in <a href="https://learninglab.si.edu/q/ll-c/pPEjlxzvSDYKI29e#r/61864">Expanding Roles of Women</a> or used alongside an existing unit of study on women’s suffrage or related topics. Sparking Civic Engagement, asks students to study ephemera from the campaign for suffrage. Students then create a campaign promotional item, such as a piece of apparel or a broadside, to take a stand on a current gender-based issue.<br></p>

<p></p>

<p>This assessment asks students to draw connections between the history of women’s suffrage in the United States and current gender-based issues, encouraging them to take a stand. First, students will study ephemera, or the ordinary, often transient objects, from the U.S. women’s suffrage movement: Among other artifacts, they will review a selection of witty banners that amplified the goals of protestors. They will also examine the resolute rhetoric of broadsides, the printed manifestos of the movement. Using these artifacts as models, students will then brainstorm current gender-based issues surfacing in their communities. Finally, students will design and create a campaign strategy and accompanying promotional materials, such as posters or apparel, to address their selected issue.</p>

<p></p>

<hr>

<p>#NPGteach #OutOfMany</p>

<p>Keywords: Suffrage, Civic Engagement, Campaign, Broadside, Postcards, Gender</p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

34

Expanding Roles of Women: Radicals

<p>In this Learning Lab collection, radical women featured in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery exhibition,<em> Out of Many: Portraits from 1600 to 1900, </em>are used as entry points to teach about the history of radicals during this time period.<br></p>

<p>From 1600 to 1900, women dramatically expanded their roles in politics and the professional sphere, including the arts. This set of Teaching Ideas explores the biographies and careers of those “radical” women who dared to create change in the cultural, political, and social spheres. Specifically, these lessons highlight Indigenous and Black activists who, despite being excluded from the broader suffrage movement, forged inroads for education and public awareness of racial inequities. The multi-hyphenate Zitkála-Šá grew up on the Yankton Sioux reservation in South Dakota. She cultivated her skill as a musician and writer, all in the face of forced assimilation at an Indian boarding school. Later, she advocated for Native American suffrage. Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells-Barnett were influential political organizers. The increasing racial terrorism inflicted upon African American men ignited their activism. They would later become leaders in the women’s suffrage movement, founding clubs and organizations that would become hotspots for political mobilization. This section also addresses the ways that women artists and intellectuals used portraiture to promote a certain “visual identity,” or the elements and stylings that shape their public image.</p>

<p>Throughout this collection, students will examine not only the portrait subjects but will also gain insight into the larger historical time period in which the subjects lived, understand how the women in these portraits lived and located agency, and reflect on the present by considering how women continue to make changes in society.</p>

<p>This collection contains three lessons that highlight radical women: "Reading Portraiture: A Different Schooling," "Engaging History: Making Inferences with Primary Sources," and "Connections to the Present: Visual Identity."</p>

<p><strong><br></strong></p>

<p><strong>Reading Portraiture: A Different Schooling</strong><br></p>

<p>Students will gain an understanding of Zitkála-Šá’s experiences as a student and teacher at Indian boarding schools, particularly regarding how those experiences shaped her cultural identity and activism. To begin the lesson, students will explore their own identities. They will then compare and contrast two portraits of Zitkála-Šá. In addition, they will analyze an excerpt from one of Zitkála-Šá’s short stories.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul>

<li>How did Indian boarding schools impact the identities of Native Americans? What are their generational effects on Native cultures?</li>

<li>How do portraits demonstrate the complex identities of individuals?</li>

<li>What can we learn about an author’s beliefs by reading their work?</li>

</ul>

<p>Objectives</p>

<ul>

<li>Students will consider the complexities of their own identities and think about how they would represent themselves in a portrait.</li>

<li>Students will compare and contrast different portraits of Zitkála-Šá to consider the facets of the subject’s identity.</li>

<li>Students will analyze and annotate a primary source document.</li>

</ul>

<hr>

<p><strong>Engaging History: Making Inferences with Primary Sources</strong></p>

<p> </p>

<p>Students will examine cultural artifacts to gain an understanding of Mary Church Terrell’s radical approach to racial equality and women’s suffrage. First, students will read a portrait of Terrell, using the “See/Think/Wonder” thinking routine to spark their curiosity. Second, the teacher will model how to investigate primary sources and record inferences on a graphic organizer. Then student groups will move through a Gallery Walk to analyze a variety of primary sources and fill out their own inferences.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul><li>How can portraits initiate a deeper analysis of a person’s biography?</li><li>What can primary sources tell us about women activists in history?</li><li>How has Mary Church Terrell paved the way for today’s activists?</li></ul>

<p>Objectives</p>

<ul><li>Students will use thinking routines to begin a historical exploration of a portrait subject.</li><li>Students will analyze primary sources to make inferences about Mary Church Terrell’s life.</li><li>Students will compare the approaches of past and present activists</li></ul>

<p></p>

<hr>

<p><strong>Connections to the Present: Visual Identity</strong><br></p>

<p>In this lesson, students will determine what constitutes a “visual identity,” or the elements and stylings that shape a person’s public image. When people appear in public, they emphasize certain traits or characteristics, such as keen fashion sense, bold speech, or winsome facial expressions. On social media and other visual platforms, people savvily use physical appearance and personality to create a public-facing self.</p>

<p>Students will examine how portraiture was used to shape or define visual identity in the nineteenth century and how it is used today. Visual identity is a strategy to convey political aims and actions, as in the collective portrayal of suffragists and writers in Eminent Women. Alternately, visual identity can heighten a public version of the self, as in the striking pose of thespian Minnie Maddern Fiske. To conclude this lesson, students will draw connections between these nineteenth-century portraits and portraits of today’s radical women.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul><li>Which Elements of Portrayal contribute to an online presentation of the self?</li><li>Which values, identities, and actions can a work of art promote?</li><li>How have some women used portraiture to further their professional and political aims?</li></ul>

<p>Objectives</p>

<ul><li>Analyze the visual identity of the historical and contemporary portrait subjects.</li><li>Identify one present-day radical woman whose politics and personhood align with those of the historical women featured in the National Portrait Gallery’s portraits of Eminent Women and Minnie Maddern Fiske.</li></ul>

<hr>

<p>#NPGteach #OutOfMany</p>

<p>Keywords: Radicals, Women, Zitkala-Ša, Indian Boarding Schools, Yankton Dakota, American Indian Women, American Indian Citizenship, American Indian Activism, Primary Sources, Mary Church Terrell, Suffrage, M Street Colored School, Visual identity, Eminent Women, Minne Maddern Fiske, portraiture, portraits, </p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

71

Expanding Roles of Women: Professionals

<p>In this Learning Lab collection, professionals featured in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery exhibition,<em> Out of Many: Portraits from 1600 to 1900 </em>are used as entry points to teach about the history of the women's work.<br></p>

<p>In the nineteenth century, women increasingly took on roles in public life. During the early Republic, Sarah Weston Seaton, the wife of a newspaper publisher, became a consummate host of political elites in her Washington, D.C., home. Women artists, such as Sarah Miriam Peale and Mary Cassatt, painted commissioned portraits of powerful individuals and ordinary scenes of domestic life, respectively. Writers like Charlotte Perkins Gilman advocated for fundamental shifts in women’s economic and social power. According to Gilman, women’s labor should not be restricted to the domestic sphere. Rather, they deserved the freedom to pursue professions outside of the household. In this collection, students will study women’s entrance into the professional sphere, where they set forth their ideas through the arts, public speaking and events, and campaigning.</p>

<p>In addition, students will examine not only the portraits subjects but will also; gain insist into the larger historical time period in which the subjects lived, understand how the women in these portraits lived and located agency, and reflect on the present by considering how women continue to make changes in society.</p>

<p>This collection contains three lessons that highlight themes relating to women and work: "Reading Portraiture: Claim, Support, Question," "Engaging History: Valuing the Work of Women," and "Connections to the Present: Tracking a Journey in the Public Eye." </p>

<hr>

<p><strong>Reading Portraits: Claim/Support/Question</strong></p>

<p>Students will gradually uncover Mary Cassatt’s life through the “Claim, Support, Question” strategy from Reading Portraiture 101. They will enter the lesson by analyzing the portrait without knowing the identity of its subject or any background information.</p>

<p>As more evidence is revealed to students, they will make truth claims about who they think Mary Cassatt was. Second, they will use evidence to support or question their claims. Students will then synthesize all the evidence they have examined in a written reflection on Mary Cassatt’s life and values. Teachers will conduct a class discussion about what they have learned. To supplement this history, Sarah Miriam Peale and Edmonia Lewis will be introduced as the predecessor to and contemporary of Cassatt, respectively. Students will have the opportunity to explore additional professional women artists from the nineteenth century to the present through a variety of extension activities.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul><li>What can a portrait tell us about someone’s life?</li><li>How can historical evidence help us make inferences about a person’s story?</li></ul>

<p>Objectives </p>

<ul><li>Students will interpret the message an artist conveys through their self-portrait.</li><li>Students will analyze and synthesize visual and written evidence to draw conclusions about their claims</li></ul>

<hr>

<p><strong>Engaging History: Valuing the Work of Women</strong></p>

<p>Students will explore the portraits and lives of Sarah Weston Seaton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Working in groups, students will identify the spaces these women carved out for political and creative work in a society that largely relegated them to the home.</p>

<p>Seaton, the wife of a prominent Washington, D.C., newspaper editor, was a keen observer and host of political life in the early Republic—all while raising eleven children.</p>

<p>Born in 1860, over seven decades after Seaton, Gilman shunned the confines of nineteenth-century domesticity. Instead, she pursued a robust career as a writer, lecturer, and artist, often addressing the topic of women’s unacknowledged economic contributions. </p>

<p>Even with their considerable racial and class privilege, Seaton and Gilman grappled with the restrictions and expectations of their times: marriage, child-rearing, running a household, and entertaining guests, among myriad other duties. By examining</p>

<p>Seaton’s and Gilman’s portraits and related primary sources, students will determine which activities counted as labor for these women.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul><li>What counts as work?</li><li>What kind of work is valued in your society? What kind of work is undervalued?</li><li>How do women locate agency, even when they are held back by a society’s norms?</li></ul>

<p>Objectives </p>

<ul><li>Use primary sources to infer the conditions of women’s lives and livelihoods.</li><li>Prepare a claim about women and work that is based on primary sources.</li></ul>

<hr>

<p><strong>Connections to the Present: Tracking a Journey in the Public Eye</strong></p>

<p>In this lesson, students will learn about contemporary women who have played prominent roles in American politics and culture.</p>

<p>To what extent do these women, especially those with proximity to power, draw on their lived experiences to fuel their platforms? By focusing on a living first lady, students will outline how women in power navigate life in the public eye.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul><li>How does prior experience shape a life in public service?</li><li>Which biographical factors inform the aims of women in politics?</li></ul>

<p>Objectives </p>

<ul><li>Track the biography of a first lady and study how prior life experiences shaped her life in the White House.</li><li>Summarize key findings from web-based research; categorize research and make judgments.</li></ul>

<hr>

<p>#NPGteach #OutOfMany</p>

<p>Keywords: Professionals, Mary Cassatt, Women Artists, Sarah Miriam Peale, Edmonia Lewis, Impressionists, Impressionism, Working Women, Sarah Weston Seaton, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Phillis Wheatley, Anne Catherine Hoof Green, Betty Friedan, First Ladies, Hillary Clinton, Laura Bush, Michelle Obama, Melania Trump, Web Research, Primary Sources, Claim/Support/Question</p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

78

Expanding Roles of Women: Suffragists

<p>In this Learning Lab collection, suffragists featured in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery exhibition,<em> Out of Many: Portraits from 1600 to 1900 </em>are used as entry points to teach about the history of the suffrage during this time period. </p>

<p>During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many women sought voting rights as the foundation of women’s rights, and they were often viewed as radical for having such a goal. As daughters and wives, women in the United States had few decision-making rights, let alone the right to own and control land, so having the power to make political decisions through suffrage was seen as extreme. When Elizabeth Cady Stanton initiated the first woman’s rights convention at Seneca Falls in 1848, some attendees expressed this concern. The struggle for women’s suffrage was rooted in the abolition movement and anti-slavery societies, where Black and white women organized together to end slavery. White suffragists learned from leading Black women abolitionists like Sojourner Truth and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who had been organizing and speaking publicly for many years before Seneca Falls. By the end of the Civil War, when voting rights for Black men were written into law, racism began to divide the suffragists.</p>

<p>Although Susan B. Anthony worked with Stanton to end slavery, they did not believe that Black men should gain suffrage before white women. In this set of Teaching Ideas, students will examine the details of this divide and discover how suffragists fought for women’s rights and social justice issues. For example, the journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett advocated for Black women’s rights, including suffrage, and protested the lynching of African Americans. Lawyer Belva Ann Lockwood not only believed in women’s right to political representation but also in their capability of holding the highest office in the land: She ran for president in 1884 and 1888.</p>

<p>Throughout this collection, students will examine not only the portraits subjects but will also; gain insist into the larger historical time period in which the subjects lived, understand how the women in these portraits lived and located agency, and reflect on the present by considering how women continue to make changes in society.</p>

<p>This collection contains three lessons that highlight the American suffragist movement: "Reading Portraiture: Striking a Pose," "Engaging History: Unity and Division Within the Women's Suffrage Movement," and "Connections to the Present: Women Presidential Candidates."</p>

<hr>

<p><strong>Reading Portraiture: Striking a Pose</strong></p>

<p>In this lesson, students step into the roles of two leaders of the American women’s suffrage movement: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Ida B. Wells. One of the most famous suffragists, Stanton was a founder of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and a prolific writer and theorist of feminist thought. Wells was an investigative journalist and newspaper editor who led an antilynching campaign and fought for women’s suffrage. In addition, she founded the politically influential Alpha Suffrage Club, which aimed to give a voice to African American women who were excluded from mainstream suffrage organizations.</p>

<p>Inspired by the suffragists’ political use of the tableau vivant, or a carefully posed, motionless scene with living actors, this lesson will ask students to closely study—and bring to life—Stanton and Wells’ portraits and polemics.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul><li>Which Elements of Portrayal lend visual power to a portrait?</li><li>To what extent does a sitter’s pose convey a sense of authority and selfhood?</li></ul>

<p>Objectives </p>

<ul><li>Study the social and historical implications of primary sources and original works of art.</li><li>Extend the analysis of nineteenth-century portraits of suffragists into a dramatic, kinesthetic interpretation.</li><li>Identify some of the primary principles of the women’s suffrage movement.</li></ul>

<hr>

<p><strong>Engaging History: Unity and Division Within the Women’s Suffrage Movement</strong></p>

<p>Students will gain an understanding of the unity and division within the women’s suffrage movement through a two-part lesson. They will enter the lesson by considering how history is told through portraits, in terms of who is represented and who is not. The notable absence of African American abolitionists and suffragists from the Coronation of Womanhood group portrait provides a launching point to investigate why these individuals were sidelined from the women’s suffrage movement. At the same time, students will learn about instances when African American and white women came together in their struggle for equal rights.</p>

<p>The first part of the lesson involves gathering background information from a short video and reading. Then, students will analyze primary sources that convey the unity within the women’s suffrage movement. For the second part of the lesson, students will do more in-depth investigation into the various perspectives and debates around strategies for achieving women’s suffrage, which exemplify division within the movement. During an interactive “Chalk Talk,” students will respond to both quotes from these historical debates as well as to the opinions of their fellow classmates.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul><li>How has portraiture been used to represent the history of women’s suffrage?</li><li>How can we account for the missing or underrepresented perspectives in history and what can we do to change the narrative?</li><li>What caused division within the women’s suffrage movement?</li></ul>

<p>Objectives </p>

<ul><li>Students will explore how portraits present history.</li><li>Students will analyze additional primary sources to understand changes within the women’s suffrage movement.</li><li>Students will investigate suffragists’ differing perspectives.</li></ul>

<hr>

<p><strong>Connections to the Present: Women Presidential Candidates</strong></p>

<p></p>

<p>Students will conceptualize portraits of women who ran for president in the late nineteenth century and more recently. They will begin by examining former presidential candidate Shirley Chisholm’s portrait. During the main part of the lesson, they will make connections between women who have run for presidential office in recent years and Belva Ann Lockwood, a suffragist who was a two-time presidential candidate in the 1880s.</p>

<p>Students will delve into women’s biographies by reading articles and conducting independent research. Afterward, they will create a portrait of a woman presidential candidate based on the Elements of Portrayal and the biographies they have read.</p>

<p>Essential Questions</p>

<ul><li>How do the experiences of historical women who ran for president compare to those of women today?</li><li>Which factors does an artist consider when creating a portrait of the president or presidential candidate of the United States?</li></ul>

<p>Objectives </p>

<ul><li>Students will investigate women’s biographies to understand what motivated them to run for president of the United States.</li><li>Students will apply their knowledge of reading portraiture and the Elements of Portrayal to create portraits of women candidates for presidential office.</li></ul>

<p></p>

<hr>

<p>#NPGteach #OutOfMany</p>

<p>Keywords: Suffrage, Suffragists, Suffragette, Women's Suffrage, Portraiture, Voting Rights, Enfranchisement, Nineteenth Amendment, Seneca Falls, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Ida B. Wells, Sojourner Truth, Abigail Scott Duniway, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Frederick Douglass, Lucy Stone, American Equal Rights Association (AERA), Belva Ann Lockwood, Shirley Chisholm, Female Presidential Candidates, Female President, Campaign, See/Think/Wonder, Strike a Pose, Tableaux Vivants, Chalk Talk, Portraiture, Making Portraits<br></p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

74

Teaching AP US History with the National Portrait Gallery

<p>This collection highlights the individuals who shaped the cultural, economic, political, and social developments of the United States from 1491 to today. The selected sitters compliment the curriculum for the College Board's <a href="https://apstudents.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-united-states-history">Advanced Placement United States History Course</a>. Open the paperclips on each portrait to find accompanying multiple-choice questions for test prep.<br></p>

<p>This collection was created in partnership between the National Portrait Gallery and Teacher Advisory Board Member and history teacher Christopher Evans.</p>

<p>#NPGteach</p>

<p><br></p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

102

Motivating Agency with Posters (Smithsonian Summer Sessions)

<p>What makes a successful poster? How can posters be used as a call to action? Inspired by Educating for Democracy's <a href="https://www.educatingforamericandemocracy.org/the-roadmap/5designchallenges/#motivatingagency-sustainingtherepublic1608806809328">Design Challenge: Motivating Agency/Sustaining the Republic</a>, this collection gathers resources and pedagogical approaches to support the 2022 <em>Smithsonian Summer Sessions</em> workshop, “Motivating Agency with Posters,” exploring techniques to invite close looking, brainstorming, and poster making.</p>

<p>Workshop facilitated by Kirsten McNally (Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum) and Briana Zavadil White (National Portrait Gallery).</p>

<p><strong>Learning Objectives</strong></p>

<p>Students will:</p>

<ul><li>Learn how to read a poster</li><li>Understand what makes a successful poster</li><li>Explore how posters are used as a call to action</li><li>Create posters that motivate agency</li></ul>

<ul></ul>

<p>#SummerSessions #NPGteach</p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

47

Exploring Women's History Through Portraiture: From Liliuokalani to Shirley Chisholm (Smithsonian National Education Summit)

<p>How can women's stories centered in the classroom? In what ways can portraiture spark civic change? This collection features portraits, strategies, and lessons for teaching about the history of women in the United States to support the 2022 <em>Smithsonian National Education Summit</em> session, "Exploring Women's History Through Portraiture: From Liliuokalani to Shirley Chisholm." With a focus on drawing connections to the present, this collection seeks to empower educators and students by introducing them to new ideas for integrating art, and civics that center on stories of women. </p>

<p>Workshop facilitated by Ashleigh Coren (Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative and National Portrait Gallery), Briana Zavadil White (National Portrait Gallery), and Amy Trenkle (Ida B Wells MS). <br></p>

<p><strong>Learning Objectives</strong></p>

<p>Educators will:</p>

<ul><li>Identify elements of portrayal in order to read portraiture </li><li>Learn about hidden histories of women</li><li>Examine the importance of sharing different historical perspectives</li><li>Collaboratively brainstorm how to integrate resources into the classroom.</li></ul>

<p>#NationalEducationSummit #TogetherWeThrive #NPGteach<br></p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

24

Our Struggle for Justice: A Digital Collaboration between the National Portrait Gallery & Capital One

<p><em>What can you do to make a difference?</em> Introducing <a href="https://npg.si.edu/visit-home/digital-engagement">Our Struggle for Justice</a>, a digital collaboration between the <a href="https://npg.si.edu/">National Portrait Gallery</a> and <a href="https://www.capitalone.com/">Capital One</a> that explores activism and social justice through biography.<br><br></p>

<p>How can you use your skills to spark conversation, create agency and inspire change? In this collection, meet individuals, past and present, from the museum’s collection whose thoughts and actions have made our nation better. Each featured individual is accompanied by thought-provoking questions, educational resources, and additional portraits to reframe the way we view activism and the causes closest to us.<br></p>

<p>Join us on <a href="https://www.instagram.com/smithsoniannpg/">Instagram</a> and <a href="https://twitter.com/smithsoniannpg">Twitter</a>, follow #OurStruggleForJustice for the latest updates, and look out for new posts each Tuesday. </p>

<hr>

<p>Through our Twitter and Instagram, we will delve into the museum’s collection to contextualize the pursuit of freedom and activism in the United States, sparking conversation and inspiring action. </p>

<p>Our country was established on two basic principles: freedom and the pursuit of happiness. However, over the course of our history, these ideals have been broken, tested and reconstructed. Many times, the onus for upholding the nation’s moral foundation has fallen to the individual rather than the majority. </p>

<p>American activism guides our nation toward its true vision, one that acts upon the ideals of its founding and celebrates the entirety of its population. And while many before us defined what it means to strive for a better America, there is no question that this work is ongoing. </p>

<p>Through Our Struggle for Justice, we will meet individuals, past and present, whose thoughts and actions have made our nation better. Though their experiences and causes vary, these people have one thing in common: they fought tirelessly against injustice, using their time, strengths and sheer will to create meaningful change. </p>

<p>In telling these stories, we aim to spark conversations around agency. Look for thought-provoking questions to reframe the way we think about activism and the causes that are closest to us. <br></p>

<p>The campaign draws inspiration from the Portrait Gallery’s collection, including the permanent exhibition The Struggle for Justice, which celebrates pioneers and change-makers in the fight for social equity. </p>

<p>One person can make a difference. In learning about these figures, we hope that you can, too. <br></p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

112

Perspectives: The Atlantic's Writers at the National Portrait Gallery

<p>This collection<em> </em>features portraits of <em>The Atlantic'</em>s celebrated authors. Each portrait is accompanied with perspectives by contemporary <em>Atlantic </em>writers who reflect on the lives and legacies of earlier ones. </p>

<hr>

<p><em>It was the spring of 1857. America was divided, and war would soon come. In Boston, some of the country's most esteemed writers gathered to launch a magazine, one that would argue against slavery and for the union. They had much in common: a profound hatred of human bondage; an equally profound love for America’s deepest values; and patrician, tripartite names (James Russell Lowell, Ralph Waldo Emerson). It was men only that day, though the founders had as an ally the most important writer in America, Harriet Beecher Stowe, who endorsed their aims but stayed away because alcohol was being served.</em></p>

<p>The Atlantic,<em> a founding statement declared, would be "fearless and outspoken" and "of no party or clique," and would cover politics, literature, science, and the arts. Its special focus on abolition widened to include racial justice and civil rights on a broad front—the themes of this exhibition. Sometimes with prescience, sometimes with false steps, the editors and contributors sought to advance an ever-evolving concept they called “the American idea.”</em></p>

<p>The Atlantic<em> today has a global readership and the range of contributors is wide. Its commitment to the idea that America is forever capable of becoming a more perfect union remains undiminished.</em></p>

<p><em>Here, contemporary </em>Atlantic<em> writers reflect on earlier ones.</em></p>

<p>-Jeffery Goldberg</p>

<p><a href="https://www.theatlantic.com/author/jeffrey-goldberg/">Jeffrey Goldberg </a>is the editor in chief of <em>The Atlantic</em> and a recipient of the National Magazine Award for Reporting. </p>

<hr>

<p>#NPGteach</p>

<p><br></p>

Nicole Vance

Nicole Vance

32