Nicole Votta

I'm a Liberal Arts major at the University of Massachusetts with concentrations in English and Art History. My areas of interest include late Gothic and early Renaissance European art, mid-19th century to early 20th century European art, and medieval through early modern Indian art. I'm also interested in mid-20th century art associated with underground or counter-culture groups or pop culture. I'm particularly interested in illustrations and book art.

Nicole Votta's collections

Communication with the spiritual in ancient to modern art

<p>This collection will examine examples

of art as a form of communication between the human and spiritual

worlds. These forms of communication may include examples of direct

communication — in which an individual or group uses art to speak

to and influence the spiritual world — as well as examples that

serve to document practices, beliefs, and the place of spiritual

practices in society at large.</p>

<p>The form and focus of these

communications expressed through art can help to explain the values

of particular cultures or individuals, or may serve to question or

enforce certain cultural beliefs. This type of art may be the

expression of the needs of a social group or culture, such as

prehistoric cave paintings that might have functioned in rituals to

ensure successful hunts or plentiful game. It may serve to enforce a

political agenda such as the <em>Law Code of Hammurabi.</em> Or it may

express an individual's personal interpretation and experience of

spirituality such as the illustrated poetry of William Blake.

However, form does not always imply the expected function: the 19th

century English painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti sometimes

drew on religious subjects or themes and much of his work has a

mysterious and mystical atmosphere. Yet Rossetti, describing his

spiritual beliefs, called himself an “art Catholic,” implying

that if he engaged in a spiritual dialog through his art, it was with

art itself (Faxon, 1989).</p>

<p>This collection will look at examples

from the prehistoric era through the early 20th century. These

examples help to contextualize the inner lives of individuals, and

the collective inner life of the cultures, their environments, wants,

needs, and values, to foster a greater appreciation of and respect

for these peoples and cultures. <br /></p>

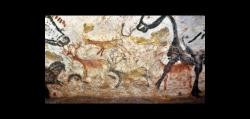

<p>Although there is only limited firm

evidence of the purpose of cave art found at sites such as Lascaux,

Chauvet, and Les Trois-Frères, scholars generally agree that it

served some religious purpose. Various theories have been proposed to

provide more specific explanations. Cave art, particularly

Paleolithic cave art, depicts almost exclusively animals. Hunting was

crucial to the survival of early humans, and it is possible that the

images were created as part of hunting rituals. Images of animals

superimposed over each other many have represented fertility rituals

aimed at increasing the amount of game animals. Some images appear to

have been deliberately scratched or gouged with spearheads — in

some cases blood was painted flowing from these wounds — suggesting

that the images may have been intended as a type of sympathetic magic

giving hunters power over and protection from large and dangerous

animals (Benton & DiYanni, 2012). </p>

<p>Other images are less easy to explain

and have given rise to controversial theories such as the bird-faced human figure in the Lascaux Shaft Scene, that

combine elements of humans with other animals in a single figure. The Shaft Scene appears to describe a narrative although the exact meaning is not completely clear. A wounded bison stands ready to charge; the animals intestines appear to be pouring out of its abdomen and a spear is shown near its hindquarters. In front of the bison is a stick figure human with a bird's face. The human figure appears to have fallen or been knocked over. Just below this odd figure is a line topped by a bird, perhaps an object belonging to the bird-faced man. This figure and others that combine humans and other animals into one figure such as The Sorcerer in Les Trois-Freres may document early humans' mythology, and could suggest

the origins of certain beliefs and practices (Curtis, 2006). </p>

<p>The meaning of the <em>Law Code of

Hammurabi</em> is less ambiguous — the spiritual and the

legal/political aspects of the culture are united. The stele dates to

approximately 1760 BCE and is divided into two sections. The lower

section, which takes up the majority of the stele, consists of the

code of laws in effect at the time. The relief at the top depicts the

Babylonian king Hammurabi receiving the laws from the god Shamash.

The implication is clear: the law itself is a religious document and

the social rules it describes are the will of the gods — and

Hammurabi whose authority is bolstered by the approval of the gods

(Benton & DiYanni, 2012). </p>

<p>The spiritual is not always a numinous

experience in a cave. Some early laws and social codes were framed as

divine communications that enforce social norms and rules — even

now, witnesses in courts are generally sworn in by placing their hand

on a Bible. Communication with the spiritual in examples such as the

<em>Law Code of Hammurabi</em> is aimed at establishing and enforcing

order and lending it a weight of legitimacy. It is as critical for

the members of an urban culture, such as Babylon, to abide by rules

to maintain peace with their neighbors as it was for the Paleolithic

peoples to ensure successful hunts. And, kings such as Hammurabi

believed it was critical to protect their power. By aligning

themselves with gods, they could borrow some of the gods' power in

the minds of the people and make rebellion or betrayal a kind of

sacrilege. Hammurabi, in fact, was declared a god in his own lifetime

(Van De Mieroop, 2005).</p>

<p>Music may also function as a form of

communication between gods and humans. In pharaonic Egypt, religious

festivals appear to have prominently involved music and dance. Music

may have been used in religious rituals to communicate with the gods,

invoke deities, or as a medium to transmit offerings. Some

instruments were associated with specific deities: the sistrum with

Hathor and Isis and the tambourine with Bes. Sistrums may have been

played during rituals associated with Hathor to invoke her — and to

placate her. Although images of deities playing musical instruments

are relatively rare in Egyptian art, Bes is frequently depicted

dancing and playing a tambourine. Unlike the other gods, Bes used

music to communicate with humans. Bes was associated with the home

and family — the front rooms of Egyptian homes appear to have

contained shrines to Bes — and he remained a popular deity among

the people throughout Egypt's history. Bes was believed to protect

people, particularly women in childbirth, by playing music to

frighten away evil spirits. Amulets of Bes dancing and playing a

tambourine appear to have been a common type of protective amulet

worn around the neck. It is worth noting that depictions of Bes

differ markedly from depictions of most other Egyptian deities: he is

represented in lively motion. In contrast to the image of Egyptian

religion based primarily on royal tombs and, therefore, focused on

death and the elite members of society, Bes was closely tied to life

and the lives of common people (Simmance, n.d.).</p>

<p>Composed by the poet Valmiki in India the fifth century

BCE, the <em>Rāmāyana</em> relates the deeds and adventures of Rama, an avatar

of Vishnu. According to J. L. Brockington, in Indian tradition the

<em>Rāmāyana</em> is designated

the <em>ā</em><em>dik</em><em>āvya,</em>

which may be translated as “the first poetic work,” and is

regularly referred to as being sung as opposed to spoken in contrast

to the <em>Mahābhārata</em>. In one version of the framework story

introducing the <em>Rāmāyana,</em> Rama is described as the perfect human

being. His behavior is therefore worth emulating, and it is likely

that as early as the first millennium BCE that was in a sense being

done literally through plays and dances reenacting the story

(Brockington, 1998). In that sense, the <em>Rāmāyana</em> represents a

complex, evolving dialog, a lived experience of both artistic and

spiritual expression. </p>

<p>Euripides'

tragic drama <em>The Bacchae</em> is another example of theater acting as a

complex dialog between the human and the spiritual worlds. The plot

of <em>The Bacchae </em>revolves around the arrival of the god Dionysos in the

city of Thebes where his ecstatic worship is opposed by Pentheus, the

king of Thebes. As Segal writes, the play is morally ambiguous and

may have been designed to implicate the audience in the action.

Although Dionysos is a disturbance to Thebes, Pentheus' response is

heavy-handed and unsympathetic. However, as the drama unfolds, the

audience that may have been rooting for Dionysos is confronted with a

climax that sees the god orchestra Pentheus' gruesome death. It is

important to note that Dionysos was a well-established and liked god

in Athens and that Classical Greek drama was written to be performed

during annual festivals in Dionysos' honor. As Vellacott writes,

during the festival a statue of Dionysos was brought from a shrine to

the amphitheater to watch the plays. As Segal notes, it is unlikely

that the play is meant to be critical of Dionysos (his actual worship

was much more restrained than depicted in the play or the myths it

was based on) but its presentation, at a fundamentally religious

festival with the god literally in the audience, could not but have

sparked another dialog within the audience, a reflection on their

relationship to the god and the sometimes overwhelming forces he

represents.</p>

<p>The

Temple of Isis at Pompeii declares both the strength of her

worshipers' belief and the endurance of her cult in the face of

repeated official sanctions. The temple was damaged in an earthquake

in 62 AD but was rebuilt by the time of the eruption of Vesuvius in

79 AD; in fact, it was the only civic building in that area of

Pompeii that had been completely rebuilt (Hackworth, 2006).

The apparent preference for a foreign goddess in a Roman city is all

the more significant in light of imperial persecutions and

prohibitions against her worship dating back to Augustus and coming

to a head in 19 CE when Emperor Tiberius exiled thousands of freedmen

who were adherents of the religion (Heyob, 1975). However, the cult

of Isis continued to flourish. By the time of Pompeii's destruction,

her worship appears to have included individuals from all classes of

society, from members of the imperial family and municipal officials

to freedmen and slaves (Takacs, 1995). The remains of the temple can

still be seen on the original site and at the nearby Museo

Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. Although Egyptian decoration was

incorporated in the design of the temple and cult objects, the plan

of the building and the style of the frescoes was Roman (Moorman,

2011). The navigium Isidis fresco appears to show a distinctly

Egyptian scene, Isis resurrecting her husband-brother Osiris, but in

a purely Roman style. The Pompeiian worshipers of Isis were part of

Roman culture but may have been seeking an opportunity to engage in

personally meaningful spiritual communication outside of the

state-sectioned venues and deified emperors (Hackworth, 2006). <br /></p>

<p>Early Buddhist art avoided direct

representations of the Buddha. The first iconic representations of

the Buddha were likely not created until approximately the 2nd

century CE in the area of Gandhara, in modern-day Pakistan, under the

influence of the Kushan emperors. After their conversion to Buddhism,

the Kushan produced distinctive images of the Buddha that drew on

Greco-Roman traditions while creating an iconographically unique

image that was clearly identifiable as the Buddha (Benton &

DiYanni, 2012).</p>

<p>Many of these early sculptures of the

Buddha depict a serene, sublime figure, perfectly proportioned and

untouched by time or the rigors of his life. However, a small group

of statues presents a radically different image of the Buddha. One of

these statues, <em>Fasting Buddha</em>, created between the 2nd

and 4th centuries CE, depicts the physical effects of the

Buddha's forty-five days of fasting and meditation before achieving

enlightenment. In an interview with <em>Hyperallergic</em> in 2016 when

<em>Fasting Buddha</em> was seen publicly at an Auctionata sale, Dr.

Arne Sildatke, Auctionata's head of Asian art, explained that

although the <em>Fasting Buddha</em> and similar images can be compared

to depictions of the crucified Jesus Christ, the Buddhas are not

images of death and resurrection. Instead, they are meant to

communicate to followers Buddhism the concepts of self-empowerment

and the overcoming of suffering, according to Sildatke. Despite the

figure's protruding bones, sunken stomach, and hollow face, the image

expresses the strength of the Buddha's will (Voon, 2016).</p>

<p>The Ajanta caves in Maharashta state,

India, contain some of the finest examples of Indian Buddhist art and

represent several centuries of complex artistic spiritual expression.

The caves were created as a monastery and decorated in the Gupta

style of sculpture and painting. The Gupta style moved away from the

Greco-Roman influence and embraced a more fully Indian style in which

characteristics of physical beauty associated with Indian art are

adapted to symbolize spiritual beauty (Benton & DiYanni, 2012).</p>

<p>The monks' work on the caves was likely

supported during its later phase by wealthy patrons, including the

5th century CE Emperor Harisena and his courtiers. These

patrons sponsored the construction and ornamentation of specific

caves to honor the Buddha and earn religious merit, as well as

worldly praise, for themselves. According to Spink, Cave 1, created

in the late 5th century CE, was sponsored by Harisena.

Cave 1 contains some of the most sumptuous and well-preserved murals

in Ajanta. It is likely that these images, including the Bodhisattva

Padmapani, are so well-preserved because Cave 1 was never used for

worship. Spink theorizes that Cave 1 was not used because Harisena

died suddenly before the cave could be dedicated. An undedicated cave

could not be used for worship; therefore, if the cave was indeed left

undedicated, Harisena would not have achieved the religious merit he

desired (Spink, 2008). In that case, Harisena's attempt to

communicate with the spiritual, to have his faith validated, and his

attempt to communicate his spiritual virtue to the human world were

both left unfulfilled.</p>

<p>Rich ornament and stylization was also

used to signify spirituality in European Christian manuscript

paintings. As Christianity spread through Europe, representations

were adapted to the local Celto-Germanic styles, which bore more in

common with the luxurious, symbolic, and stylized Byzantine art than

the naturalistic Greco-Roman tradition. The <em>Book of Kells</em> is

an illuminated gospel created c. 800 CE by Irish monks. A figure of

St. John on one folio is an exercise in elaborate stylization, a

purely two-dimensional figure made up of patterns of decorative

lines, emphasizing the image's spiritual rather than physical reality

(Benton & DiYanni, 2012).</p>

<p>An illuminated gospel such as the <em>Book

of Kells </em>was not merely a book — as the chalice used in Mass is

not merely a cup — it was created as a sacred object (Calkins,

1983). Like the images in Chauvet cave or the ceremonial sistra used

in Egyptian religious ceremonies, it formed part of the necessary

accouterments of communication with the spiritual. And, therefore,

its form and image took precedence over its physical practicality

(Calkins, 1983). In that light, the entire object itself, not only

individual folios, can be seen as a translation of spiritual

experiences and a vehicle for spiritual communion. </p>

<p>Liturgical music has been a key part of

Christian ritual since the earliest days of the religion. Most early

Christian music was woven into the services and often consisted of

chants based exclusively on scripture. Over time, the scope of music

in Christianity grew and original pieces were composed. One notable

composer in the Early Middle Ages was Hildegard of Bingen

(1098-1179). Beginning in early childhood, Hildegard experienced

intense visions. She entered a community of nuns when she was eight

and became a poet, composer, and playwright (Benton & DiYanni,

2012).</p>

<p>Hildegard also wrote several books

detailing her mystical visions and theological instructions derived

from them. One of these, <em>Scivias,</em> contained sections that

Hildegard later adapted to the <em>Ordo Virtutum, </em>a sacred music

drama (King-Lenzmeier, 2001). The plot revolves around the struggle

between the devil and the Virtues for a human soul. The <em>Ordo</em>

was not written to be performed as part of the Mass or liturgy and

does not depict biblical events: the allegorical story is adapted

directly from her personal visionary experiences (Potter, 1986). When

performing the <em>Ordo,</em> the nuns were embodying and participating

in Hildegard's visions by bringing these invisible spiritual

experiences into the human world (Davidson, 1992). </p>

<p>The Unicorn

Tapestries were made in Brussels c. 1500 and depict the

hunt, capture, and death of a unicorn. The tapestries may have been

made as a wedding gift and may have been intended to communicate a

multilayered message that combined romance and fertility with

Christian doctrine (Benton & DiYanni, 2012). The chivalric

tradition of courtly love had introduced the idea that romantic love

was a symbol of God's love: Marie de France's <em>Eliduc</em> employs

this symbolism to suggest that when two individuals loved each other

completely they could leave each other for God, separating to live in

different religious communities (Potkay, 1994). In <em>The Unicorn

Tapestries, </em>Margaret B. Freedman explores the complex

interweaving of secular and religious messages encoded in the

tapestries, including references that syncretize polytheistic deities

into Christian mythology. For example, the fountain in the tapestries

may be a symbol of the Virgin Mary, who was compared to a fountain in

many medieval hymns, as well as Venus and Cupid, who were frequently

depicted holding court in gardens dominated by a fountain. The highly

detailed flora in several of the tapestries also simultaneously

references Christ and Venus. In Freedman's analysis, the tapestries

can be understood as symbolizing and communicating the doctrines and

values of the overlapping Christian god of heaven and the god of

love, a concept that was well-established by the late medieval

period. In the context of the tapestries as a wedding gift, this dual

meaning is perfectly appropriate to express, reminding the newlyweds

of their spiritual, personal, and social duties and rewards.</p>

<p>In 15th century Florence, a

renewed interest in and availability of Classical Greek and Roman

scholarship fueled the development of Neoplatonism, a new school of

philosophy that sought to merge the principles espoused by the

Classical Greek philosopher Plato and the Roman philosopher Plotinus

with Christian spirituality. Platonism and Christianity are dualistic

and perceive a separation between the physical and the spiritual that

humans should strive to breach. According to Neoplatonist thought,

this could be done by recognizing the spark of the divine — the

work of God — in beautiful things in the physical world; therefore,

the love of beauty was a form of worship (Benton & DiYanni,

2012). Florentine Renaissance ideals of beauty were heavily indebted

to Greco-Roman traditions that emphasized harmony, rationality, and

balance. Therefore, in art and architecture, this could be performed

by using geometry as a symbol. </p>

<p>The elaborate geometrical floor pavings

in the Medicis' private chapel, the Chapel of the Magi, may be a

deliberate geometric code that communicated Neoplatonic ideals and

functioned as a type of devotional communication. Cosimo de' Medici,

who commissioned the chapel, and several of the artists and

architects involved in the design and construction of it were closely

involved with the founding of the Accademia Platonica in Florence, an

influential group of scientists, artists, and philosophers and which

was the cradle of Neoplatonism. The chapel's pavings following

distinctive, complex geometrical patterns and ratios tied to

Neoplatonic thought. The chapel was constructed for the use of the

Medici family and those close to them — it was not intended as a

place of worship for the public. Therefore, the Medicis and the

artists, scientists, and intellectuals close to them could freely

express in a precise geometric language certain beliefs and modes of

thinking that were not completely orthodox. In the carefully

measured, sumptuous marble pavings of the chapel, they could

demonstrate theories of elevated scientific and religious though:

divine harmony communicated through mathematics (Bartoli, 1994).</p><p>The

17th century English poet John Donne combined sexual

language and spiritual subject matter to express his concept of

ecstatic love. In this concept, an individual achieves unity of body

and soul and reaches spiritual truths through sexual union with

another individual they love. The soul is capable of awareness and

growth only through love, and during sex the souls of the individuals

mingle, each soul gaining greater knowledge of itself in relation to

the body. The individual is then a complete self: a being that is a

synthesis of its physical and spiritual aspects (Thommen, 2014). </p>

<p>This

concept is described in Donne's poem "The Extasie":</p>

<p>We

see by this it was not sex,

<br /> We see we saw not what did move; <br />But

as all several souls contain

<br /> Mixture of things, they know not

what,

<br />Love these mix’d souls doth mix again

<br /> And makes both

one, each this and that </p>

<p>“The Extasie,” therefore, communicates Donne's own

understanding and experience of spiritual communion. Like the

Neoplatonics, Donne's efforts to interact with the spiritual are

focused on resolving the perceived conflict between the physical and

the spiritual by seeking the divine in the physical — but uniting

body and soul by being united with another individual.</p>

<p>Communication with the spiritual is also blended with sensuality

in Gianlorenzo Bernini's <i>Ecstasy of St. Teresa</i> (1645-52). The

subject of the sculpture, St. Teresa of Avila, was famous for her

ecstatic visions as described in her writing, particularly her c.

1567 <i>Autobiography. </i>Teresa described a process of mental

prayer that resulted in spiritual union with God and produced visions

and intense physical and emotional responses. As quoted by Thommen,

Eleanor McCann pointed out that St. Teresa and Donne's descriptions

of communication with the spiritual through the experience of

physical ecstasy and union are, despite the author's differences,

remarkably similar.</p>

<p>Bernini's sculpture is based on the episode from St. Teresa's

<i>Autobiography </i>when an angel appeared to her and thrust a

golden spear into her heart, producing an intense pain and an

“infinite sweetness” that she described as the “sweetest

caressing of the soul by God” (Benton & DiYanni, 2012). The

sculpture, therefore, is in the interesting position of relating

mystical communication third hand. Unlike the nuns in Hildegard of

Bingen's community, Bernini had no direct contact with St. Teresa and

his translation of her experience was inevitably colored by his own

experiences and personality and the preferences of his patron.

Although Bernini emphasized the sensuality of St. Teresa's

experience, the sculpture occupies a supernatural sphere, distinct

from the related sculpturing groupings that are placed firmly in the

physical world and the space occupied by the viewer (Wittkower,

1980). The viewer is invited to witness the point of contact and

communication between the physical and the spiritual (Boucher, 1998).</p>

<p>In <i>The Book of Urizen,</i> published in 1794, English poet and

painter William Blake communicated a profoundly personal, visionary

spirituality that expressed his major moral and philosophical

concerns. Blake, like Hildegard of Bingen and St. Teresa of Avila,

experienced visions. He saw himself as a prophet and believed that

the duty of a poet was “To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the

immortal Eyes of Man inwards into the Worlds of Thought” (Benton &

DiYanni, 2012).</p>

<p><i>The Book of Urizen </i>is a creation myth structured along the

lines of Genesis but with Blake's Urizen in place of God. Urizen is a

god of reason and logic and law — a deity of pure materialism,

enslaved and enslaving who creates the world so that he may have

something to rule. Urizen represents both dogmatic, essentially

materialistic religious laws and Newtonian reason. To Blake, these

were both forces that blind humans to the spiritual by trapping and

circumscribing human imagination, thereby preventing them from

communicating with the spiritual, creative world that would otherwise

be their birthright (Frye, 1990). By creating <i>The Book of Urizen</i>

and his other illuminated books of poetry and painting, Blake

attempted to communicate his experience of the spiritual and warn of

the consequences of either rejecting personal communication with the

spiritual and imagination or of ceding that direct, personal

experience to a higher, worldly authority.</p>

<p>Communication between the human and the spiritual is not always

easy nor does a familiar form always imply the expected function.

These points are illustrated in the works of the English poet

Christina Rossetti and her brother the painter and poet Dante Gabriel

Rossetti. </p>

<p>Christina was deeply religious and often used her poetry to

explore both the rewards and struggle she associated with faith.

Unlike St. Teresa of Avila, Hildegard of Bingen, or William Blake,

Christina's experience of the spiritual was not mystical. Rather than

communicating with the spiritual through ecstatic visionary

experiences, Christina's efforts to communicate and achieve union

with the spiritual were the result of the effort of her faith, and

that effort, and her doubts, are expressed in her poetry. In “Alas,

my Lord,” (1874), Christina describes the difficulty of this

process and expresses her doubts as well as her desire for spiritual

affirmation — some communication, a response from the spiritual,

that her efforts are not in vain (Avery, 2014).</p>

<p> Alas my Lord,

<br />How should I wrestle all the livelong night

<br />With

Thee my God, my Strength and my Delight? </p>

<p> How can it need

<br />So agonized an effort and a strain

<br />To make

Thy Face of Mercy shine again?</p>

<p> How can it need

<br />Such wringing out of breathless prayer to

move

<br />Thee to Thy wonted Love, when Thou art Love?</p>

<p>In contrast, her brother Dante Gabriel was not a practicing

Christian, although he used Christian iconography and language,

particularly in his early works. Dante Gabriel referred to himself as

an “Art Catholic,” implying that his interest in the imagery of

encounters with the spiritual was largely aesthetic (Faxon, 1989). In

addition, he often used Christian iconography and language in the

context of secular love poems (Roe, 2010). In Dante Gabriel's art,

such as <i>The Girlhood of Mary Virgin</i> (1848-1849),

representations of the spiritual were not strictly religious but

rather an iconographical shorthand for the artist's sincere, personal

communication with their imagination. Particularly in his early

career when he identified as a member of the Pre-Raphaelite

Brotherhood, he believed that medieval art was more sincere, more

closely connected to the natural world, in opposition to the British

Academic tradition embodied by Sir Joshua Reynolds, which he believed

was formulaic and insincere (Faxon, 1989). Therefore, the religious

subject matter so prominent in medieval art took on a new meaning and

the spiritual was transferred from the Christian God to the artist's

quest for genuine inspiration. </p>

<p>The Dream of Geronitus, Op. 38, composed by Edward Elgar in 1900,

is a powerful sonic portrait of an encounter with the spiritual. Set

to the text of a poem by John Henry Newman, it describes the death of

a man, Gerontius, and his soul's journey to the throne of God to

receive judgment. A dramatic and technically challenging piece, it

explores communication with the spiritual as a psychologically

complex, and not always pleasant, experience. The rapture Gerontius

experiences is counterpointed by the appearance of devils and his own

doubts that his soul is worthy to face God. The Judgment scene, in

fact, depicts that ultimate communication with the spiritual as an

almost unbearable experience. For the scene when Gerontius beholds

the glance of God and receives judgment, the score instructs: “For

one moment, must every instrument exert its fullest force.”

(Burton, 2003).</p>

<p>In 1974, The Dream of Gerontius figured heavily in <i>Penda's Fen,</i>

a film written by David Rudken and directed by Alan Clarke for the

BBC. The film's protagonist Stephen, writes about The Dream of

Gerontius in the beginning of the film, which then unravels his

nationalist and orthodox Christian certainty through visionary

experiences that lead him to reject his former beliefs. Stephen's

encounters with the spiritual challenge the priggish patriotism and

the national and moral myth he embraced, embodied by a middle-aged

couple who have successfully campaigned to ban a film exploring Jesus

as a man rather than as a god. At one point Stephen plays the

Judgment scene from The Dream of Gerontius on the organ in his

father's church, triggering a vision of cracks appearing in the

church floor, the crucified body of Jesus, and a voice commanding

Stephen to unchain Jesus from the strictures of conservative

Christianity. Later, he experiences a vision of King Penda, the last

pagan king of England, and, grasping that his culture is ultimately a

hybrid one comprised of a mingling of various religions, languages,

and peoples, rejects his former beliefs (Sandhu, 2014). The

experience is as unsettling for the viewer as it is for Stephen. in

<i>Penda's Fen</i> the spiritual intrudes on assumptions and

certainties and by irrupting reality leads both Stephen and the

viewer to question their assumptions and demands that they take part

in a wider, richer communication with the spiritual and the world.</p><p><br /></p>

<p><br /></p>

<p><strong>References</strong></p>

<p>Avery, S. (2014). Christina Rossetti: Religious poetry. Retrieved

from

<a href="https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/christina-rossetti-religious-poetry">https://www.bl.uk/romantics-an...</a><br /></p><p>Bartoli, M. T. (1994). A Neoplatonic

pavement. In The Chapel of the Magi: Benozzo Gozzoli's frescoes in

the palazzo Medici-Riccardi Florence (p, 25-28). New York: Thames and

Hudson.<br /></p>

<p>Benton, J. R. & DiYanni, R. (2012).

Arts and culture: An introduction to the humanities. Upper Saddle

River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.<em></em><br /></p>

<p>Boucher, B. (1998). Italian Baroque sculpture. London: Thames & Hudson.<br /></p><p>Brockington, J. (1998). The Sanskrit

epics. Boston: Brill.</p><p>Burton, J. (2003). The Dream of Gerontius - Sir Edward Elgar

(1857-1934). Retrieved from

<a href="http://www.choirs.org.uk/prognotes/Elgar%20Gerontius.htm">http://www.choirs.org.uk/prognotes/Elgar%20Gerontius.htm</a><br /></p>

<p>Calkins, R. G. (1983). Illuminated

books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.<br /></p>

<p>Curtis, G. B. (2006). The cave

painters: Probing the mysteries of the world's first artists. (2006).

New York: Knopf.</p>

<p>Davidson, A. E. (1992). Music and

performance: Hildegard of Bingen's Ordo Virtutum. In The Ordo

Virtutum of Hildegard of Bingen: Critical studies (p. 1-29).

Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University.<br /></p>

<p>Faxon, A. C. (1989). Dante Gabriel

Rossetti. New York: Abbeville Press.</p>

<p>Freeman, Margaret B. (1983). The

Unicorn Tapestries. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.</p><p>Frye, N. (1990). <i>Fearful symmetry</i>. Princeton: Princeton

University Press.<br /></p>

<p>Hackworth, P., L. (2006). The freedman

in Roman art and art history. Oxford: Cambridge University Press.</p>

<p>Heyob, S. K. (1975). The cult of Isis

among women in the Graeco-Roman world. Leiden: E. J. Brill.</p>

<p>King-Lenzmeier, A. H. (2001). Hildegard

of Bingen: An integrated vision. Collegeville, Minnesota: The

Liturgical Press.<br /></p>

<p>Moorman, E., M. (2011). Divine

interiors: Mural paintings in Greek and Roman sanctuaries. Amsterdam:

University of Amsterdam Press.</p>

<p>Potkay, M. B. (1994). "The Limits

of Romantic Allegory in Marie de France's Eliduc," Medieval

Perspectives, 9 (1), 135-145.

<a href="http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/55697230/limits-romantic-allegory-marie-de-frances-eliduc">http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/55697230/limits-romantic-allegory-marie-de-frances-eliduc</a><br /></p>

<p>Potter, R. (1986). The “Ordo

Virtutum”: Ancestor of the English moralities?. <em>Comparative

Drama, 20</em> (3), 201–210. <a href="https://www.jstor.org/stable/41153244">https://www.jstor.org/stable/41153244</a><br /></p>

<p>Roe, D. (2010). Introduction in <i>The Pre-Raphaelites from

Rossetti to Ruskin</i> (p, xvii-xxxvi). London: Penguin.<br /></p><p>Sandhu, S. (2014). Penda’s Fen: A lasting vision of heresy and

pastoral horror. <i>The Guardian.</i> Retrieved from

<a href="https://www.theguardian.com">https://www.theguardian.com</a><br /></p><p>Segal, C. (2001). Introduction. In

Euripides, Bakkai (3-32). New York: Oxford University Press.</p>

<p>Simmance, E. (n.d.) Communication

through music in ancient Egyptian religion. University of Birmingham.

Retrieved 2/4/2019 from

<a href="https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/connections/Essays/ESimmance.aspx">https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/connections/Essays/ESimmance.aspx</a>.</p>

<p>Spink, W. (2008). Ajanta lecture: Korea

2008. WatlerSpink. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from <a href="https://www.walterspink.com/ajanta/ajanta-lecture">https://www.walterspink.com/ajanta/ajanta-lecture</a><br /></p>

<p>Takacs, S., A. (1995). Isis and Sarapis

in the Roman world. Leiden: E. J. Brill.</p>

<p>Van De Mieroop, M. (2005). King

Hammurabi of babylon: A biography. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing. </p>

<p>Vellacott, P. (1959). Introduction. In

Aeschylus, The Orestian trilogy (9-40). New York: Penguin.</p>

<p>Voon, C. (2016). The raw expression of

a rare, emaciated Buddha. <em>Hyperallergic. </em>Retrieved February

21, 2019, from

<a href="https://hyperallergic.com/344879/the-raw-expression-of-a-rare-emaciated-buddha/">https://hyperallergic.com/3448...</a><br /></p>

<p><span class="announcementBody">#AHMC2019</span></p>

Nicole Votta

Nicole Votta

22